Chapter 4 Incentives for Innovation

The data revolution for sustainable development is fundamentally about using new, frontier technologies to produce data, conduct analysis, generate insights, and disseminate results that might support our progress towards a more sustainable future. Frontier technologies are constantly changing but include artificial and machine intelligence, robotics, sensors, drones, cutting-edge spatial technology, and insights derived from telecommunications data. In addition, as part of the data revolution, efficiencies are being derived from lower-tech approaches such as using citizen-generated data and smartphones to speed up existing survey-based approaches (see Box 6).

Box 6: Using Frontier Technologies to Support Sustainable Farming in Latin America

Image 4: Surveyors in Mexico collect data from farmers through the MasAgro program. Source: CIMMYT

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) offers farmers useful information to make timely and better-informed decisions in Colombia, Guatemala, and Mexico. The data from CIMMYT aims to increase agricultural productivity and income, help farmers adopt sustainable practices, and adapt to climate change. To achieve this objective, CIMMYT focuses on monitoring, evaluation, and accountability, using innovative field research practices and frontier technologies to monitor, analyze, and understand Latin America’s agri-food systems.

For example, under the MasAgro program in Mexico, CIMMYT generates data on sustainable agriculture from nearly 150,000 plots (Liedtka et al. 2017). Extension agents undertake field surveys with farmers who describe important crop cycle dates, management practices, inputs used, costs incurred, yields achieved, and more. Field technicians enter the information received in an electronic log developed by CIMMYT called the MasAgro Electronic Log. They also load geographic information onto ODK Collect, an open data collection system. All submissions are subsequently saved and stored on CIMMYT’s servers for further cleaning and interpretation.

The survey-based data describing crop management practices and yields are then pooled and combined with weather records and soil readings. Thorough descriptions of the conditions in which the crops grew complement the data gathered to help make correlations between yields and income achieved. Empirical modelling techniques are also used to look for correlations or patterns that show limiting factors and optimal sustainable management practices for each plot. Technicians then go back to farmers and provide them with a comprehensive analysis of the advantages and shortcomings that their specific practices had. Farmers also receive individual sustainability scores. To offer farmers across Mexico even more specific and timely agricultural recommendations, CIMMYT recently developed an app for the Android operating system (AgroTutor) that complements the work of extension agents.

Data gathered has been used by the Mexican government to support its recent Maize for Mexico strategy, which aims to increase maize yields while protecting native biodiversity and traditional farming methods (Govaerts forthcoming). The data was also used to inform the National Development Plan 2019-2024, specifically the plans and budget for 2.8 million small and medium farmers who have been identified as potential beneficiaries of Mexico’s Agricultural Production for Wellbeing program (Narváez Narváez 2017).

Written by members of CIMMYT

In Counting on the World, we discussed the potential for frontier technologies to support safer systems for data sharing (e.g. through end-to-end encryption services), but their applications are endless. For example, satellite and drone data are being integrated with other sources of data to map ecosystem extent; satellite imagery and telecommunications data are being combined with census records to produce more accurate and timely population, migration, infrastructure, and housing estimates; and telecommunication and sensor data are being used to track informal commuter patterns, transport systems, and economic opportunities[1]. But the majority of these new technologies and approaches are being used exclusively by private industries and, to a lesser extent, academic institutions, largely in the Global North (Martin 2005). We need to move towards a system that enables the equitable sharing and exchange of technology for the public good. This chapter recommends a digital ecosystem: a network of technological platforms that enable rapid transfer of methodologies, technologies. and algorithms between public and private entities in support of sustainable development. But before we can stand up such a system we also need more human exchange. We need epistemic communities to come together to explain their new data collection methodologies, investigate their merits and demerits, and find ways to make their methods more accessible to those who most need technical assistance.

A. Thematic Collaboratives for Methodological Exchange

To encourage widespread innovation, the uptake of new data sources, and new technological capacities, we need to put in place the right operating frameworks, as discussed in Chapter 2. But we also need better systems to encourage interoperability; greater accessibility to new methods, technologies and techniques; and more capacity development and training. Without strong systems in place, the uptake of these exciting technologies by governments will be inefficient and piecemeal at best.

By way of example: To help systematize new innovative methods and to increase their accessibility, TReNDS is actively supporting the data collaborative POPGRID. POPGRID aims to bring together many of the old and new population estimate providers, from governments, to academic institutions, to multilateral organizations. These stakeholders are being brought together to discuss new methods for monitoring population and change, rigorously assess the validity and robustness of those methods, and make them more accessible to countries in need of better population estimates (e.g. as a tool between decennial census rounds or in the absence of a census). Methods being discussed include satellite imagery-based estimates, estimates taken from telecommunications data, other forms of social media and digital data, and – most fundamentally – the classic, survey-based census. Ultimately, the consortium aims to help clarify the utility of new methods and approaches for different policy purposes and regions, making it easier for countries to sort through what is available and decide which new methods might make the most sense for their specific context.

These approaches could easily lend themselves to a variety of other core data and indicators that are essential for sustainable development monitoring, such as poverty mapping, urban growth and change, ecosystem monitoring, and more. New approaches, such as citizen science, can support these efforts (see Box 8). In this instance, CIESIN, TReNDS, and the GPSDD are acting as the secretariat of the POPGRID initiative. Such an institutional arrangement could easily be applied to other sectors, with UN custodian agencies or leading academic institutions convening epistemic communities and national government representatives to establish standards and guidelines for assessing new methods and develop mechanisms through which to make them more accessible and responsive to countries’ needs.

Box 7: Interoperability

The data revolution for sustainable development is not just about access to frontier technologies and new approaches. It is also about improving the quality of our data systems, and more specifically, the interoperability of those systems. As discussed in Counting on the World, “Data interoperability is one of the biggest barriers to effective public use of private data – particularly with regards to disaggregation, as data need to be in a comparable format and/or use comparable standards if they are to be overlaid or combined” (TReNDS 2017). It limits the sharing of private and public data, but also the sharing of public data between agencies and government departments.

Ultimately, interoperability “is the ability to join-up and merge data without losing meaning’” (Joined-up Data Standards Project 2018).” As GPSDD notes, “In practice, data is said to be interoperable when it can be easily reused and processed in different applications, allowing different information systems to work together. Interoperability is a key enabler for the development sector to become more data-driven” (GPSDD 2019).

Across public and private spheres, data interoperability is a huge challenge. Fortunately, it is a solvable one. As noted by GPSDD and UNSD, “The technologies and methods needed to make data speak to each other already exist. The most serious impediments to interoperability often relate to how data is managed and how the lifecycle of data within and across organizations is governed” (GPSDD 2019). The solution is a relatively simple one: more coordinated, centralized, standardized data processes, under an evolved NSO, and a more inclusive global statistical system (as discussed above). But there is only so far that policy and regulation can go. We must also create incentives for the private sector to align the standards used for their data technologies, production, and insights.

B. Moving Towards a Digital Ecosystem to Encourage Open Innovation

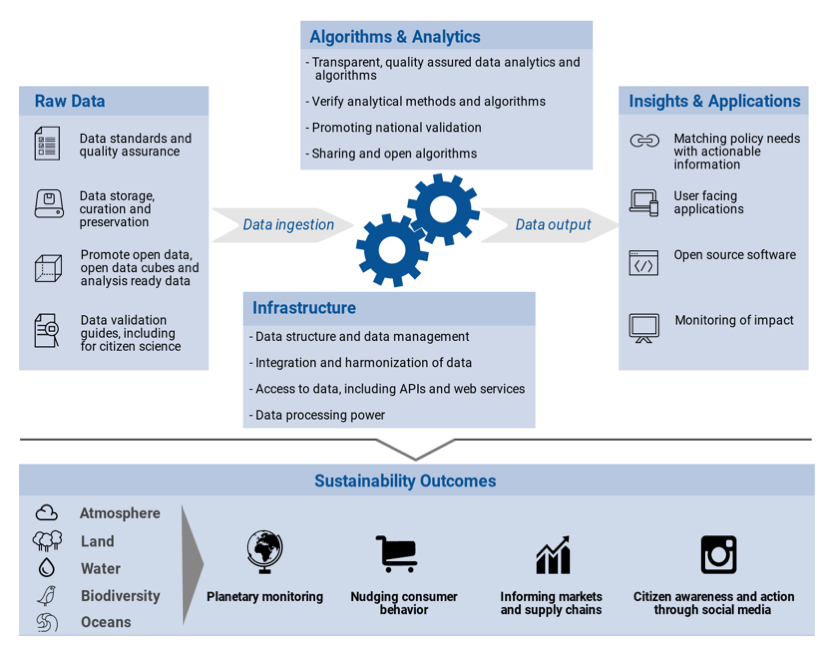

The end goal of such collaboration and exchange should be the creation of a digital ecosystem, as proposed by the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) (Figure 4): “‘a complex distributed network or interconnected socio-technological system’ with adaptive properties of self-organization and scalability” (UNEP 2019). In essence, this would be a series of interconnected digital platforms that connect data on different themes, making it comparable, accessible, and open for those seeking to use data for sustainable development purposes. The platforms would enable data to be connected to publicly available algorithms that could enable the production of insights; for example, the latest satellite imagery could be automatically combined with deforestation algorithms to look at daily tree loss and provide real-time estimates from new data sources the minute they become available. Through such a system, governments, companies, and NGOs could derive immediate insights that help them to design effective policies and processes. Being a distributed system, anyone could contribute and, through group participation, it should encourage a “race to the top” where the best possible methods and data sources become the ones most frequently used. It could also help to overcome government and corporate manipulation of data, thereby providing an automated check-and-balance of sustainable development measures.

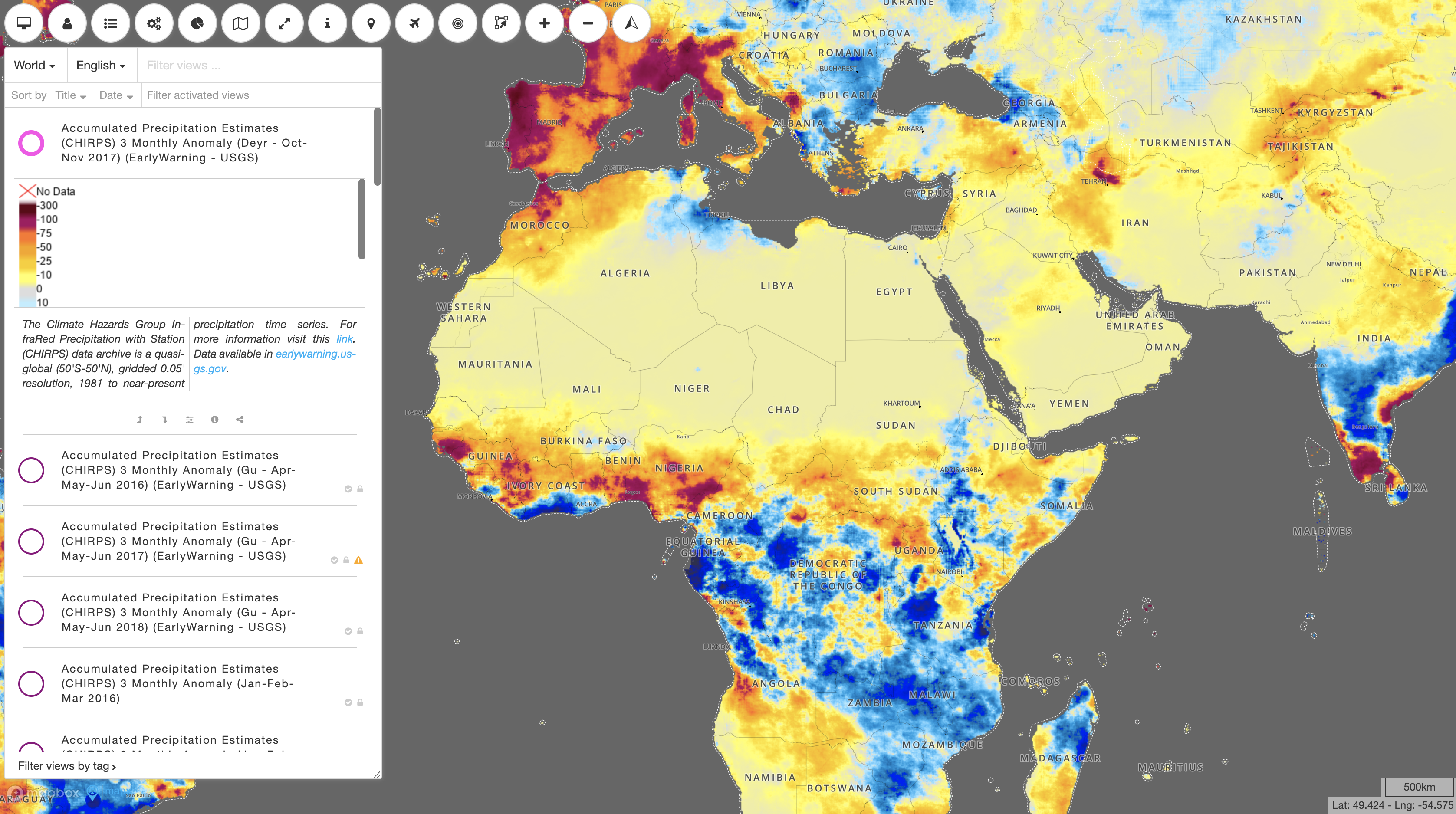

Figure 3: MapX is an example of an open source product that could contribute to the digital ecosystem (e.g through the UN Biodiversity Lab). Here, MapX provides accumulated precipitation estimates in Africa. Source: MapX

UNEP proposes that the digital ecosystem support environmental monitoring, but it could well be applied to the broader sustainable development agenda – for example, to monitor urban sprawl, infrastructure development, and more.

A key point in the UNEP proposal is that we need to create a new incentive structure and infrastructure to encourage private actors who currently monopolize digital technologies to share their information, thereby overcoming data and digital asymmetries between countries and between the private and public sectors. A key component of this incentive structure would be private company access to public data, with which they could better understand new markets and opportunities, while concurrently ensuring the protection of privacy and confidentiality.

“It is time for stakeholders in all domains to unite in building an open digital ecosystem of data, algorithms and insights in order to provide actionable evidence on the state of the environment and interactions between the economy, society and the environment.” (UNEP 2019)

Although a compelling investment case will need to be made for this, it will also need to rest upon a new social contract among companies, governments, and citizens “where mutual obligations and responsibilities are spelled out. The cost of doing business anywhere in the world should be the release of relevant non-commercial data into the global data ecosystem that can be used to measure SDG progress” (UNEP 2019). Another sticking point is likely to be how to foster trust to enable safe data access and sharing. Open source software may be one solution but, as discussed in Chapter 2, better understanding of legal arrangements, contracts, and frameworks is also essential to take such an infrastructure to scale.

To take forward this recommendation, UNEP proposes the UN Science-Policy-Business Forum on the Environment as the primary incubator for the practical implementation strategy. TReNDS proposes this be broadened to also include a social and economic science and policy advisory body, such as an UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) working group, with participation from crucial external partners (such as private company representatives and academic representatives) and coordinated by the GPSDD. This ecosystem approach should look to coordinate with and capitalize upon existing initiatives and infrastructure, such as the Global Platform for Data, Services and Applications, currently being advanced by a committee under the GWG. But most central are national governments, which should lay the foundations for such a system by making publication of non-commercial data a core operating principle for all private data providers operating in their country. Governments should also lead by example, making all public data open by default while respecting the privacy and confidentiality conditions noted above.

Figure 4: The UN Environment Programme’s proposed digital ecosystem. Source: Campbell and Jensen (forthcoming)

Box 8: Using Broad Forms of Data: The Potential Offered by Citizen Science

Image 5: More and more citizen science programs are joining the data ecosystem, such as Sustainable Coastlines’ Litter Intelligence, which collects long-term, open access scientific data on marine litter. Source: Sustainable Coastlines

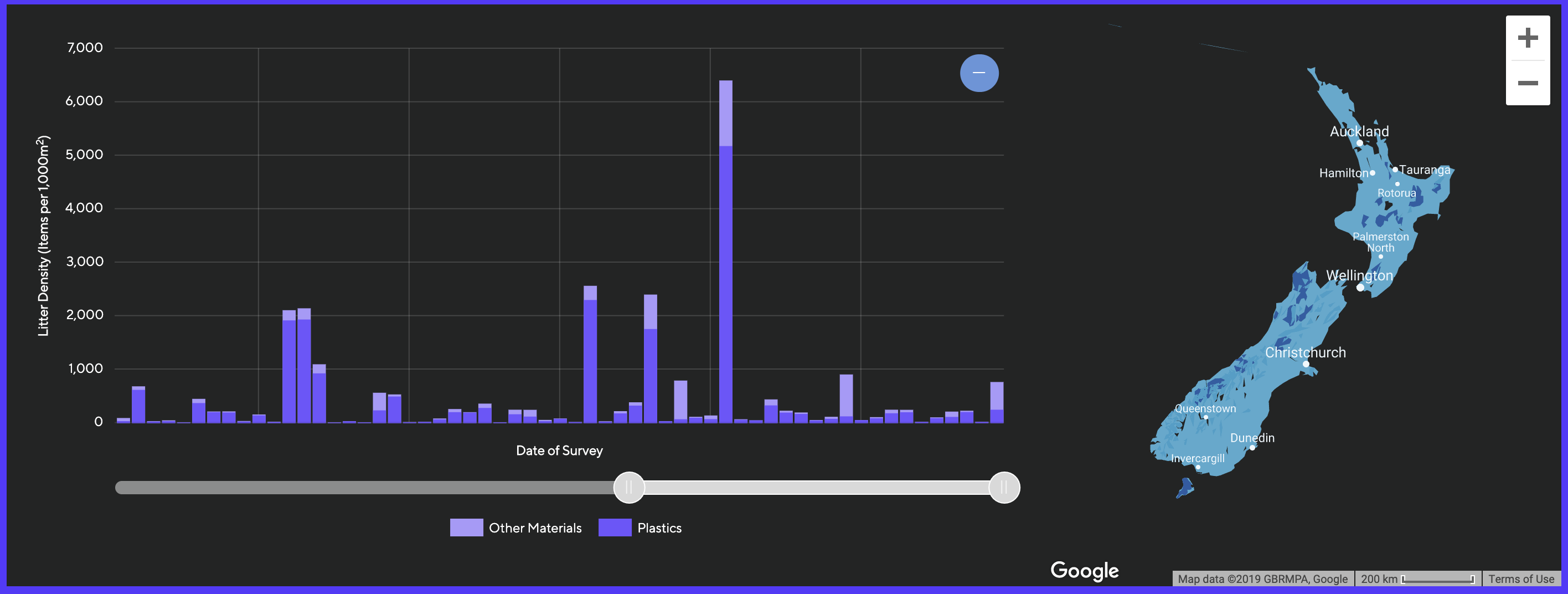

Figure 5: Explore the data collected by Litter Intelligence at litterintelligence.org. Source: Litter Intelligence

In the 2017 edition of Counting on the World, we focused on encouraging greater uptake of citizen-generated data (CGD) by NSOs. Two years on, there has been progress in the citizen science domain in systematizing approaches towards CGD.

CGD are data that people or their organizations produce to directly monitor, demand or drive change on issues that affect them (Piovesan 2017). Citizen science, another term to describe CGD, refers to public participation in scientific research in its broadest definition. Even though a wide variety of definitions is used to describe the term citizen science, they all encompass two main concepts: public participation and knowledge production.

Citizen science can differ across research fields and in terms of design processes, participation levels, and engagement practices. There are top-down approaches aimed at systematic investigation and trying to achieve certain research objectives, or more bottom up, community-driven practices for collecting evidence to influence policy.

Citizen science has great potential for contributing data to the SDG monitoring and reporting process. There are already examples of citizen science informing the SDGs, such as the following indicators on protected areas (Fritz et al. forthcoming):

15.1.2. Proportion of important sites for terrestrial and freshwater biodiversity that are covered by protected areas, by ecosystem type

15.4.1. Coverage by protected areas of important sites for mountain biodiversity

Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs) are sites designated as significantly contributing to the global persistence of biodiversity (UNSD 2017b). 21% of the world’s KBAs are fully, and 44% are partially, covered by protected areas (UN Environment World Conservation Monitoring Centre, International Union for Conservation of Nature and National Geographic Society 2018). The largest subset of KBAs is formed by Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas (IBAs) that are identified using data on birds (Birdlife International 2017).

Citizen science projects such as eBird collect data on bird distribution, abundance, habitat use, and trends. eBird volunteers from around the world gather around 7.5 million bird observations on a monthly basis, which has led to contributions of more than 100 million bird sightings per year (Cornell Lab of Ornithology n.d.). eBird, in addition to many other bird monitoring and biodiversity citizen science projects (e.g. iNaturalist, etc.) contribute to the IBA monitoring scheme managed by Birdlife International.

In addition to global reporting, citizen science is also informing national-level SDG monitoring efforts. The charity group Sustainable Coastlines is delivering Litter Intelligence, a large-scale citizen science program to collect long-term, open access scientific data on marine litter, used to scale up solutions to this problem. From its headquarters in Aotearoa, New Zealand, the group is collaborating with the Ministry for the Environment, Statistics New Zealand, and the Department of Conservation on implementing the program.

The data collection methodology uses a localized adaptation of the UNEP/Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission marine litter survey guidelines as co-developed by the collaborating government departments, who also worked together in the project design phase in 2016 and 2017. Statistics New Zealand has applied the principles and protocols for producers of Tier 1 statistics to the data framework to ensure that the data are of an appropriate standard for use in environmental reporting by government bodies nationwide, as well as for international reporting (including the SDGs). In March 2019, Sustainable Coastlines submitted its initial Litter Intelligence data set to the Marine Environment reporting team, comprising 29 detailed litter surveys conducted between October 2018 and March 2019 by citizen scientists at 21 official beach monitoring sites around New Zealand (Howitt 2019). As of this writing the data set has passed through all the quality assurance checks required by Statistics New Zealand and will be included in the official environmental report Marine 2019, slated to launch in October 2019 and produced by the Ministry for the Environment and Statistics New Zealand.

The potential offered by citizen science to SDG monitoring is not limited to these examples. IIASA is currently leading a research effort, together with a team of experts and in partnership with UNEP, as part of the SDGs and Citizen Science Community of Practice under the European Commission H2020-funded WeObserve project and the Citizen Science Global Partnership’s SDGs and Citizen Science Maximization Group. The objective of the research is to provide a detailed analysis of the current and potential contribution of citizen science to SDG monitoring. Such efforts do not only put forward a concrete proposal and an evidence-based action plan to address the current data needs, but also demonstrate the value of collaborations among the citizen science community, custodian agencies, and NSOs, while at the same time placing citizen involvement and evidence-based policy making at the heart of the SDG process. In addition, they have the potential to increase awareness and capacity within the citizen science community on the SDGs and vice versa.

Collaborations among NSOs, custodians, and the citizen science and CGD communities are also important for developing robust methodologies for assuring the quality and accuracy of citizen science data and assessing their representativeness. Structures such as an Interagency Expert Group on CGD (as suggested by TReNDS in the previous edition of Counting on the World) or UNEP’s Science-Policy-Business Forum on the Environment can also be used to build support, demonstrate the value of citizen science to countries and the statistical community, and provide an official body that could create guidelines on using citizen science data.

Written by Dilek Fraisl, IIASA, TReNDS member

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank Jillian Campbell (UNEP) and Camden Howitt (Sustainable Coastlines, Litter Intelligence Program) for their contributions to this piece.

Actions

-

Encourage Member States, working with UN custodian agencies and the UN Statistical Commission, to stand up thematic collaboratives for methodological exchange where new approaches to measurement of specific indicators and issues can be evaluated, debated, and categorized to make them more accessible to NSOs and other relevant government departments.

-

Members of ECOSOC, working with the UN Science-Policy-Business Forum on the Environment and the Global Platform, should advance the concept of a digital ecosystem for sharing data, algorithms, and infrastructure. This should build upon and complement the Global Platform for Data, Services and Applications being advanced by the UN Statistics Division and the UN Global Working Group on Big Data for Official Statistics.

See The Global Biodiversity Information Facility (www.gbif.org), POPGRID (https://www.popgrid.org), and Digital Matatus (http://www.digitalmatatus.com/intro_full.html). ↩︎