Chapter 3 The Legal and Policy Scaffolding

In Counting on the World, TReNDS recommended the UN Statistical Commission and wider partners adopt nine principles identified by the IEAG to “facilitate openness and information sharing, and protect human rights” (IEAG 2014). We also recommended expanding efforts to establish joined-up data standards for official and non-official data, e.g. relating to data design, collection, analysis, and dissemination. These recommendations could be achieved through revisions to the Fundamental Principles of Official Statistics (as led by the Friends of the Chair group) and through the inclusion of non-governmental actors in thematic or epistemic discussions on SDG indicators. These are important processes through which to bring national and international data providers together, and can help the community set common frameworks and practices. However, such processes can only go so far. Effective data stewardship across government, private, and non-governmental actors requires common policies, legal frameworks, and terminology[1].

A. Terminology

Institutional mechanisms that facilitate data partnerships are essential, but only if all of the actors around the table speak the same language. Without internationally-agreed terminology, countries can use wildly different methodologies and achieve very different results. Controlled vocabularies are an essential component of technical data standards as they provide a precise and agreed definition of what is being measured or counted. For example, the term “affected” within a disaster risk reduction context might have a different meaning based on an individual country’s classification of who is directly or indirectly affected. This can impact the response from government agencies and non-governmental organizations, influencing related data and how its collected and analyzed. The lack of agreed hazard terminology is a prime example of how, without clear terminology, governments struggle to collate, report, and share information as per their commitments under the SDGs, Paris Climate Agreement, and Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction.

Fortunately, in the case of hazards, a Technical Working Group on Sendai Hazard Definitions and Classification – co-facilitated by the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction and the International Science Council – is working to develop new hazard definitions and classifications, working with a wide variety of stakeholders to ensure the list is robust and reflects the full spectrum of local and regional terminology. Where ambiguities exist on terminology in the SDG indicator list, UN custodian agencies and the Inter-agency and Expert Group on Sustainable Development Goal Indicators (IAEG-SDGs) should convene broad epistemic communities and aim to forge consensus as a matter of urgent priority.

B. Open Data Policies

A useful policy mechanism through which to encourage cooperation and trust is an open data policy, which encourages the promotion of data that is “licensed for re-use by anyone, free of charge, subject only to discretionary provisions that the source be attributed or that future distribution of the data be sublicensed under a share-alike provision on the same or similar open terms” (ODW 2019a).

As quantities of data have increased around the world, calls for publicly-produced data to be made freely available have also increased. New movements and organizations around open data (Open Data Charter), open government (Open Government Partnership), and open knowledge (Open Knowledge International) have emerged over the past two decades to support the public’s right to information. This right is further supported by the Fundamental Principles of Official Statistics, a set of ten principles that lay out the professional and scientific standards for NSOs. The first principle, which arguably incorporates the remaining nine and embraces the core principle of open data, states: “Official statistics that meet the test of practical utility are to be compiled and made available on an impartial basis by official statistical agencies to honor citizens’ entitlement to public information” (UNSD 2013).

In addition, in recent years the World Wide Web Foundation have strongly advocated for data to be “open by default,” i.e. publicly disclosed unless there is a legitimate reason for it not to be. There is an emerging trend towards this; as of 2016, 112 countries had passed legislation governing access to information, up from only 14 in 1990 (World Wide Web Foundation 2016; Right2Info 2012; Loesche 2017). In countries with robust access to information laws (which enable public access to information held by public authorities), the concept of making data open by default then emerges as a preferred policy approach for implementing and operationalizing the legal duty to proactively disclose information and data by creating a presumption in favor of openness. Over 65 countries have committed themselves to this approach by signing up to the Open Data Charter, whose first principle is “open by default” (ODW 2019a).

Box 4: Putting Countries in the Driver’s Seat: Open Data at the National Level

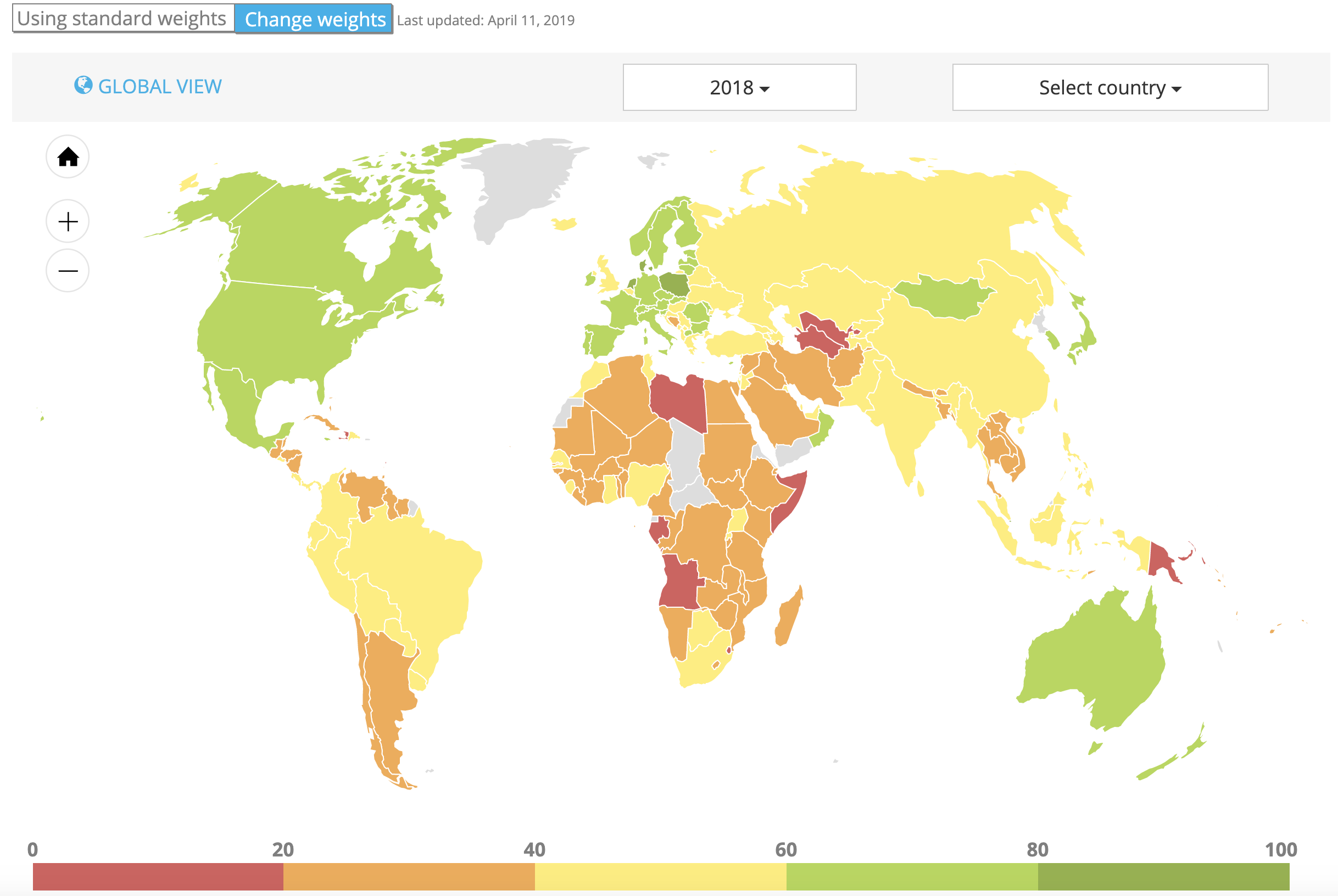

Figure 2: Open Data Watch’s Open Data Inventory illustrates the current state of openness around official statistics, including progress at the country level. Source: Open Data Watch

The Open Data Inventory (ODIN) 2018/19 is the fourth edition of an index compiled by Open Data Watch to assess the coverage and openness of official statistics in 178 countries (ODW 2019b). The purpose of ODIN is to provide an objective and reproducible measure of the public availability of national statistics and their adherence to open data standards.

Results from 2018 indicate that national statistical systems are becoming more open. Most of the countries that made the greatest progress over the last year did so by improving the openness of existing data. Between 2017 and 2018, the openness elements with the highest average improvement were terms of use or data licenses (with an average increase of 20 points on a scale from 0 to 100) and metadata availability (with an average increase of 10 points). Some of the countries that made the largest positive changes amended or adopted open terms of use or developed a new data portal.

One of the countries that made such progress was Morocco, whose openness score increased from 25 to 65 between 2017 and 2018. After the publication of the 2017 edition of ODIN, Morocco’s High Commission for Planning set forth to create a data portal that would allow users to better access existing and new data. Combined with a newly constructed open terms of use, the result was a dramatic increase in openness. All openness criteria improved in 2018 except metadata availability, although the High Commission has stated that work in this area is on its future agenda.

The improvements to both data availability and openness in Morocco were a result of government coordination, political support, and adequate funding. It highlights what is possible when both human and financial resources are available and allocated to the data agenda. Several other countries have had similar success with their open data efforts, including Jamaica, Singapore, and Oman. Exerting minimal efforts to adopt open terms of use or publish in non-propriety formats has resulted in major gains.

However, as noted by ODW, open by default is a complicated concept that requires a more nuanced approach to determine where exactly the boundaries of what can and cannot be shared lie. “For instance, taking the example of aggregated official statistics mentioned in the paragraph above, while it is important that the public have access to statistical products (‘information’), to what degree are they entitled to the underlying data that are used to produce them? Under an open by default approach, does an NSO have a duty to share the microdata that are used to compile official statistics? If so, in what form?” (ODW 2019a).

It concludes that opening data through an open by default approach should be the preferred method for administrative authorities seeking to be as open as possible. Yet it is also crucial that the limits of this approach are understood and that guidance is provided to practitioners to enable and empower them to take informed decisions about which data should be open, and which closed. In instances where open policies are not possible, e.g. due to confidentiality concerns, governments can still encourage collaboration between public and private entities within a secure operating framework by establishing trusted user frameworks, data protection acts, and data sharing agreements.

Box 5: The Next Frontier of Open Data Policies: Microdata

Microdata are data on the characteristics of a population – such as individuals, households, or establishments – collected by a census, survey, or experiment. These data can be aggregated up to the regional or national level into indicators that allow countries and other stakeholders to monitor the SDGs and determine whether development efforts have their intended effect and reach the people who need them most. Granular information about vulnerable populations, however, may get lost in data at the aggregate or macro-level. Microdata are therefore critically important for promoting the disaggregation of indicators for the monitoring of the SDGs. Because microdata potentially contain information about individuals, which can be a threat to privacy, the opening up of microdata by governments is even more contested than the move for open macrodata. However, to harness the full potential of microdata, they must be open and accessible.

Despite a consensus that open microdata are beneficial, practical guidelines on how to implement open microdata do not exist. Microdata are collected using many different instruments and processes, and countries typically use a mix of instruments with different structures and frequencies combined with statistical methods. Classifications, coding, and scales used to report data may also differ between instruments and countries and over time. These combined complications make them more difficult to standardize and develop guidelines for than macrodata. Further, depending on the type of instrument used and characteristics of the data included, restrictions may be placed on the data; the microdata made available to the public may be modified to preserve confidentiality, subject to restrictions on their use, or have limitations on access to users. In many cases, no access to microdata is provided at all. This lack of coherence of the openness and availability of microdata can lower use by researchers and the public at large and prevents microdata from being used to unlock innovation by public and private actors. It also creates mistrust in data among those that have or have not been given access. Often researchers complain that large development agencies that have privileged access do not do enough to use or share these data.

In order to address these challenges, a research project by Open Data Watch is analyzing the metadata stored alongside microdata for 15 African countries and deriving a set of standards that countries or international agencies can use to evaluate their current practices, as well as establishing guidelines for the dissemination of existing or future microdata. Using tools like this, policymakers can improve the legal and policy framework surrounding microdata and ensure data serves its purpose as a public good.

C. Legal Frameworks

Not only do a lack of shared terminology and unclear policies prohibit productive inception conversations, but they considerably hamper formal legal partnerships and constrain the enabling environment for data sharing between entities[2]. Law and regulatory frameworks are where the rubber hits the road: where the exact details of who produces, owns, uses, controls, and stores the data are specified.

In more than 100 countries worldwide, data protection acts help to ensure that data held by private companies are subject to the same protections as those held by governments – for example, to uphold individuals’ privacy. They also help establish a common operating framework valid not only for data protection, but also for effective data sharing (Banisar 2019). However, that leaves more than 90 countries and territories worldwide without effective common frameworks. In such instances, the bilateral legal agreements put in place by private companies and public entities to share information become exceptionally important as they dictate how data will be exchanged, who will own it, who will store it, how privacy will be maintained, and more.

In 2018, TReNDS, in partnership with the World Economic Forum, University of Washington, and the GovLab at New York University, launched an initiative called Contracts for Data Collaboration (C4DC), aimed at improving understanding of the specific legal conditions that can enable effective data sharing between public and private entities, as well as across public entities. Our objective is to create an online library of data sharing agreements, with supporting analysis, to help data collaborators learn from past examples and craft effective agreements. Ultimately, we aim to lower the barriers to negotiating such agreements and thereby encourage more public-private data partnerships. The project addresses a range of audiences, including governments and NSOs, but also business, civil society, and academia. We aim to provide these groups and others with a range of tools to facilitate understanding of the opportunities and challenges related to formalized data sharing, underpinned by written agreements. Data collaboratives have to negotiate questions around data rights, ownership, use, control, and risk. Developing trust and an understanding of the range of legal possibilities are important to navigating these questions.

In Colombia, for example, Cepei has piloted an innovative project with the Bogotá Chamber of Commerce to reconcile local data sources on economic growth, infrastructure, and industrialization now, available to Colombia’s national statistical office (Rodriguez 2019). Although the collaboration has been a success, securing the necessary arrangements proved more difficult than initially anticipated. Cepei was able to analyze the Chamber of Commerce data in less than two months, but the process of negotiating a one-and-a-half-page agreement to enable them to do so took over six months (Ibid). Similarly, Development Gateway – which promotes data-driven development solutions – regularly finds that it takes three to four months to negotiate data sharing agreements (DSAs) with its partners (Hatcher-Mbu 2019). Flowminder took an entire year to negotiate a three-way data sharing agreement in Ghana among themselves, Vodafone, and Ghana Statistical Services (Li 2019).

DSAs may be challenging to negotiate but they generally share common elements; they all concern the routine sharing of data sets between organizations for an agreed purpose. They can also involve a group of organizations arranging to pool their data for specific purposes. Within the context of the C4DC project, an analytical framework has been developed to parse the many terms in DSAs into logical categories along a list of easily accessible questions: Why is the agreement formed? Who is involved? What are the data? How will data actions be managed? When will data actions take place? Where will these actions take place, and are there jurisdictions to consider? These overarching questions lead into more detailed analysis that is intended to document structured data actions and facilitate user understanding of real-life DSAs. An open repository of analyzed agreements will lend clarity around data action issues that can result in high transaction costs and delays when negotiating the terms of a DSA.

As of this writing, over 40 agreements have been analyzed using the framework. The initial sample has included concise MOUs and extensive legal agreements. The agreements span Africa, Europe, North America, and Latin America, and cover data describing issues from climate change to poverty. They concern data being shared between businesses, governments, and civil society, and capture arrangements at the local, national and international levels. While accessing a wider pool of agreements has at times been difficult, this highlights the potential value of the project. Initial analysis and key informant interviews have underscored the difficulties in negotiation and some of the variety in approaches. Many collaboratives take a less formal route and only form non-binding agreements. By bringing issues of accessibility, complexity, and the time it takes to negotiate agreements into the open, the repository will help users gain a better understanding of the issues at stake and make better informed decisions when negotiating and entering into new agreements.

To further catalyze such work and make such tools more available to national governments, it should be supported and advanced by the UN Global Working Group (GWG) on Big Data for Official Statistics (a partnership of Member States and international agencies established at the 45th UN Statistical Commission, working together to investigate the benefits and challenges of big data for sustainable development), who should ultimately aim to develop a set of legal guidelines relating to public-private data collaboration.

Actions

-

Where ambiguities exist on terminology in the SDG indicator list, UN custodian agencies and the IAEG-SDGs should convene broad epistemic communities and aim to forge consensus as a matter of urgent priority.

-

Countries should put in place clear open data policies that commit governments to make data open by default with explicit exemptions relating to confidentiality of microdata, thereby supporting public sector data sharing and collaboration.

-

The UN Global Working Group on Big Data for Official Statistics should amplify work initiated by TReNDS, the GovLab, the University of Washington, the World Economic Forum, and others on legal standards for public-private data sharing – for example, deepening the analysis, sharing replicable best practices, and eventually developing guidelines on effective legal agreements for collaboration.

Assuring the responsible and effective use of data requires that an organization develops necessary skills and procedures. Both business and government have recognized the need for data stewardship: the creation of mechanisms for responsibly acquiring, storing, and using data (SAS 2014; USGS n.d.; Rosenbaum 2010). Data stewardship depends on data stewards, or individuals throughout an organization who can address issues of data access, are accountable for data quality, and can advocate for data management, among other responsibilities (USGS n.d.). In this way, professionalizing the role can help bring predictability and scale to data collaborations (GovLab 2019). Moreover, stewardship suggests a fiduciary responsibility and a consideration of the public interest (Rosenbaum 2010). And its value extends beyond partnerships with the private sector; applying the core principle of data responsibility in the work of NGOs can help improve humanitarian responses (UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs and the Centre for Humanitarian Data 2019). ↩︎

As recognized in the CTGAP, which called on national governments to revise statistical laws and regulatory frameworks in order to develop a mechanism for the use of data from alternative and innovative sources within official statistics. ↩︎